Cubans evoke the transcendent historical event that took place in 1878 in the Mangos de Baragua, where General Antonio Maceo along with Manuel de Jesus Calvar, Vicente Garcia and a small group of combatants gave a dignified and revolutionary response to the opprobrious Zanjon Pact, which represented a surrender of the Cuban arms and meant a peace without independence.

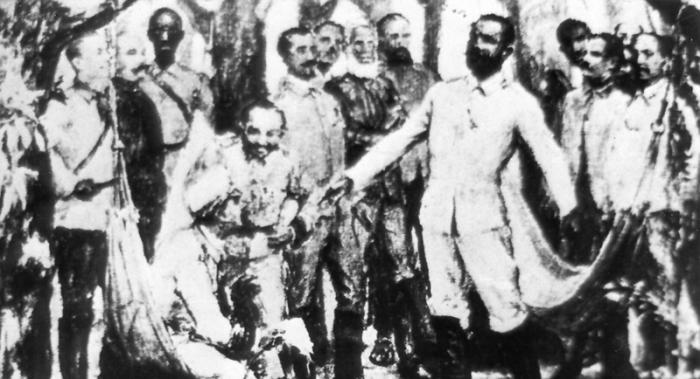

On March 15, Generals Antonio Maceo Grajales and Arsenio Martinez Campos met and there, among flattery from his counterpart, the Bronze Titan communicated to the Spanish military that they did not agree with the signed pact, because it did not contemplate the independence of Cuba, nor the abolition of slavery.

When leading the historical Baraguá Protest, Antonio Maceo and his companions raised the banner that others had dropped and they did it with firmness and good sense; it was not a romantic gesture, nor the result of the exalted passion of the insurgent leader, but the expression of a vertical refusal to accept defeat.

The act has a singular political meaning in the history of the fight of the Cuban people for their emancipation, because, with his attitude, Maceo represents the passage of the political direction of the revolution, from the hands of the representatives of a social class that had demonstrated its incapacity to reasonably conduct the war, to other’s, willing to continue it until achieving the political objectives that had taken it to the manigua: the independence and the abolition of the slavery.

The Protest of Baraguá meant a serious attempt to continue the armed struggle against Spain and highlighted the principle of never surrendering, of not giving up in the face of difficulties and setbacks; it constituted the express reaffirmation of the love for independence and social justice, and the purest revolutionaries, who refused to let the sword fall, were in charge of putting it on record.

With justice, José Martí, apostle of Cuban independence, described it as «the most glorious of our history».